BIL speaks with Paul Knepper, who has authored a deep, definitive look at the career of late Hall-of-Famer Moses Malone.

At six feet and ten inches, it was perhaps difficult for Moses Malone to disappear in a crowd. But some believe that it has become the fate of his otherwise sterling professional legacy.

Malone, who passed away in 2015, had one of the busiest careers in the history of the sport: upon his professional debut with the American Basketball Association’s Utah Stars in 1974, Malone became the first man to take the floor with a pro team straight out of high school. A 19-year NBA career ensued thereafter, one primarily known for its time in Houston and Philadelphia while also finding time in Buffalo, Washington, Atlanta, Milwaukee, and San Antonio.

Malone became historic for all new reasons in that span, taking home three Most Valuable Player awards, a dozen All-Star Game invitations, and a championship ring/MVP title from the Philadelphia 76ers’ 1983 triumph over the Los Angeles Lakers. He became renowned for his paint prowess, pacing the league in second chances on six occasions, one of only three (alongside Wilt Chamberlain and Dennis Rodman) to do so. Even so, some amateur and professional observers believe that Malone’s name has been lost to the passage of time, surprised that it’s not often included in discussions centered around the greatest of all-time.

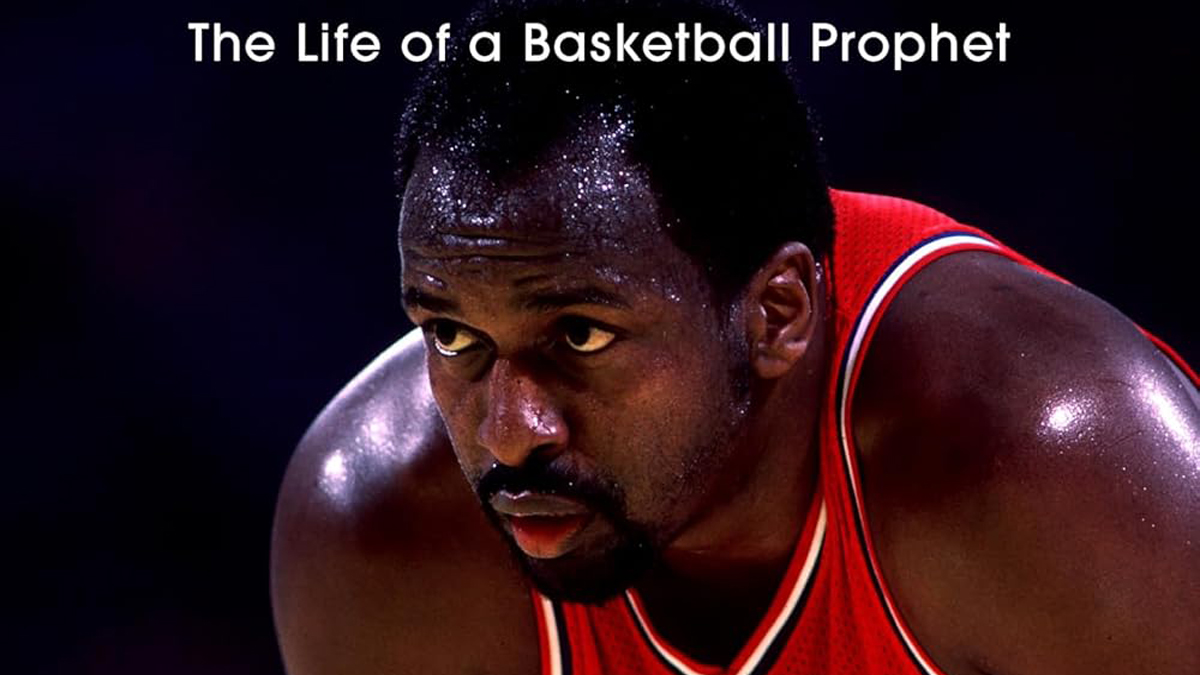

Looking to combat that consensus is author Paul Knepper, who previously penned “The Knicks of the Nineties: Ewing, Oakley, Starks and the Brawlers That Almost Won It All.” Knepper is set to release “Moses Malone: The Life of a Basketball Prophet,” which will document Malone’s incredible career and rise to glory. Pre-order the book on Amazon here.

In anticipation of the book’s Nov. 1 release, BIL speaks with Knepper below.

Why was now the best time to tell Moses Malone’s story?

PK: I think he’s just gotten kind of lost to history. I am a huge basketball fan, and I follow the discourse around the game and around the history of the game, and nobody’s mentioned him, nobody talks about him anymore. So I wanted to kind of bring his story back into the into the light, and for people to hear it. I think younger generations, in particular, just have no idea. They’re not watching clips of him on YouTube, as they do with other players of his caliber, or other players from older generations. He was more one to to tell his own story. So I kind of felt that it was time to fill the younger generations, particularly, in on what a great and really impactful player he was.

Why do you think Moses has slipped through the cracks of NBA history, especially considering his incredible impact on the game and the prevalence and availability of highlights and videos from the era?

PK: That’s a great question, and it’s something I grappled with. I really devoted the preface of the book to that, as to why he has slipped through the cracks. The people I talked to, who played with him or against him, a number of people said to me “I never would have imagined that Moses Malone be underrated one day.”

I think there are a number of reasons, but I kind of boiled it down to three main ones: [First], there was no flash to Moses game. He didn’t soar to the basket like Michael Jordan or [Julius Erving]. He wasn’t a wizard with the ball, like a Magic Johnson. He wasn’t bombing 30-foot shots like Steph Curry. He didn’t even have a signature shot, like a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar skyhook or something like that.

Even back then, I think, SportsCenter wasn’t leading off with highlight reels with images of Moses Malone grabbing offensive rebounds. Moses was kind of the lunch pail superstar. His greatest attribute was his work ethic, his relentless drive. It wasn’t necessarily individual plays that stood out. It was kind of this constant, steady stream, this just indomitable force that just kept coming and coming and coming. I think it’s hard to capture that in highlights. I think younger generations of fans aren’t pulling up clips of that the way they might more with guys who have more fantastic moves or plays or whatever it is.

I think another big factor is place. What I mean by that is most of Moses’ contemporaries, the great players of his generation, they typically spent their whole careers with one, maybe two, teams. You know, Magic played his whole career with the Lakers, and [Larry] Bird, his whole career with the [Boston] Celtics. Isiah, his whole career with the [Detroit] Pistons. Dr. J spent his whole NBA career with the [Philadelphia] 76ers. Kareem played for two teams over a 20-year career.

Moses, for a variety of reasons, played for nine different teams across two leagues over his career. He’s loved and appreciated in Houston and Philly in particular. His jersey is retired in both places, but he kind of wasn’t there long enough. I think he’s best known for Philly because he won a championship there, but only spent four seasons in Philly. So while he’s loved and respected there, he’s not as loved and respected as Dr. J or Allen Iverson, who were there for a decade. He’s not, kind of, celebrated in those cities the same way, or associated with any one city in the same way as a lot of his peers.

I think the last thing is Moses didn’t really give a damn how he was perceived. He didn’t play the media game. He was very gruff with the media. He had no interest in being famous, no interest in stardom, and I think that hurt him. I think it hurts him now, because back when he played, before social media, before the internet for a lot of his career, even before cable television exploded, it was the sportswriters who created the mythology around our athletes, and none of the sportswriters got to know him. He didn’t allow it, and frankly, a lot of them flat out disliked him. I think that affected the way he was covered. He never let people in.

Moses played with a scowl on his face. Who else played with a scowl on their face? Michael Jordan. Kobe Bryant. But Michael and Kobe, when the games were over, they’d sit at that press conference and they’d flash a million, billion dollar smile, right, and you saw a little different side of them, even if that was choreographed. It also led to a great deal of endorsement opportunities, which also kind of embeds them in the culture, puts brings them into people’s homes, makes people more familiar with them, makes them more likable.

Moses, I think, because of the way he carried himself and because he had a bit of a speech impediment, didn’t get those endorsement opportunities, either. I think he wasn’t portrayed like a lot of people, like a lot of his peers were back in at that time. I think, to some extent, some of those writers are still around, and don’t reminisce about him the same way they might Magic Johnson or someone like that.

With that in mind, how do you feel Moses would’ve fared in today’s NBA, where success relies on, for lack of a better term, antics both on and off the floor?

PK: I think he would have been okay. I think it would have been similar, I think he just wouldn’t have engaged. I think he wouldn’t have been on social media, he wouldn’t have gotten many endorsements.

I think there are guys like that [today]. I think Nikola Jokic is like that, maybe not quite as gruff, but I think Jokic has no interest in the fame and he’s not looking to sell himself. Maybe, going back a little bit, Tim Duncan was very much like that, right? Tim Duncan won five championships, he’s maybe one of the 10 greatest players of all time, but he kind of went under the radar. He hasn’t been out of the game that long yet, but still, people aren’t talking about him the way they talk about Kobe or even Allen Iverson.

So I think Moses, I don’t think he would have changed. I think he would have been the same, the same Moses. I think he just would have been one of these superstars who’s not getting or receiving a ton of attention.

Has that gruffness hurt his case for remembrance, especially considering plenty of other legends of the game have been warmly recalled despite switching teams?

PK: I definitely do. I think it affected the way he was portrayed and perceived at the time. I think people’s memories, people who were around then, maybe don’t think of him quite as fondly as some others.

But, again, I think it goes back to the endorsement thing, too. I think he didn’t kind of embed himself in the culture the way a lot of players of his caliber can. You think of, actually, a guy he mentored, Charles Barkley, Charles Barkley was the opposite. Barkley loves the spotlight. He loves the camera. Moses had a better career than Charles Barkley. He was probably a better player. But Charles is on, still on TV and TNT. Even if he wasn’t Charles, he’s out there, he’s out and about and and he talks to people and he smiles, and he does tons of interviews and podcasts and all that. Moses didn’t do that and wouldn’t be doing that now. I definitely think that affects the way he’s thought of and remembered.

Out of all his accomplishments, which do you feel Moses was the most proud of?

PK: That’s a great question. I think it’s the championship. Winning the championship in 1983, I think, more than all of his individual statistics, because Moses was a team-first guy. He prioritized winning and that was kind of the crowning achievement of his career, more than anything he did on an individual level.

It was a huge success individually, too: in that the year he won the championship with the 76ers in 82-83, he was the MVP of the league, and he was the MVP of the Finals. So he got the individual accolades as well. But I think, I think winning the championship was the pinnacle of his career.

If there’s a lesson that modern NBAers could take from Moses, what would it be?

PK: Humility, definitely humility. That was something that really jumped out of me in researching the book and talking to teammates and something I came to really admire about him.

As one person, actually a friend of his from high school, told me, he said, when Moses started winning MVPs and winning a championship, and I contend, he was the best basketball player in the world for a few years, this guy said to me, “Everybody changed the way they looked at Moses, but Moses never changed the way he looked at himself.”

I thought that was very profound and accurate. You hear from so many guys who played with him, guys I talked to who were second-round draft picks, who may or may not have made the team, they talk about how Moses welcomed them into the fold and took them under his wing and guided them.

I heard over and over about how he didn’t act like a superstar. He didn’t expect extra attention. He didn’t expect any special perks. He wasn’t demanding of anybody. I heard over and over again that he treated the 12th man at the end of the bench the same way he treated Julius Erving and I think that extended beyond the team: he treated the janitor in the arena the same way he treated Julius Erving despite three MVP awards and a championship and all the different accolades.

I think that’s very hard to do, and very rare, because everyone does start treating you differently. It’s hard to not see yourself differently. But I I heard it too much from too many people to think that it was a facade. I think he really somehow managed to remain humble. I think that’s even harder in today’s generation when Moses was the first guy in North American sports, to make $2 million a year. Yes, this is in 1982, $2 million a year. Now you got guys now are making 50 and $60 million a year.

The money has just gone to a whole other stratosphere, of course, and that’s not taking into account the massive endorsements, that’s just their basketball salary, God knows how many millions more in endorsement money. So I think it may be even harder to maintain that humility now, but I think it kind of demonstrated his decency as a person.

You’re talking about guys like Mike Dunleavy, Clement Johnson, Major Jones. Major Jones and Moses were best friends until Moses died. That just kind of shows you, he’s like, oh, I’m only going to hang out with the superstars. He felt just as comfortable, he may have actually felt more comfortable with the role players. I think Moses very much viewed himself as a grinder. He had a quote at one point where they asked him if he thought he was the best player in the in the game, and he said no. He goes, “I don’t consider myself the best player in the game, and I don’t really care if I am. I want to remembered it as the hardest-working player in the game.”

He kind of prided himself on his work ethic. I think that kind of ties into the humility. I think he maybe just continued to focus on where he is, what he’s accomplished. He always focused on the work and I think that kept him motivated and grounded.

How did Moses put the “V” in MVP?

PK: More than anything, he was just this imposing, physical force. He didn’t have the size of [Shaquille O’Neal]. Moses was 6’10, yes, he was very strong, but he didn’t dominate in that he was so much stronger than everyone but he kind of wore you down with his work ethic.

I don’t know if it made the book, but there’s a line from Bill Lyon, who was an old writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer. His line was “Moses was the greatest player, greatest basketball player in the world, for the most elemental of reasons. He tried harder than everyone else.” He had a work ethic that would put Pete Rose to shame and he, I heard from so many people, just wore you down.

There’s an old player named Otto Moore. He wasn’t a big time player, but he became friends with Moses. He said he compared Moses to a wolf, because a wolf is always is on the hunt, and the wolf doesn’t stop hunting until it catches his prey. He said that was Moses. He was just relentless.

He just kept coming and coming and coming. He could score at a very high level. His rebounding, that was his calling card. He was the best rebounder in the game, the best offensive rebounder ever. But, just, collectively, he was talented. He was a very intelligent player. But more than anything, he just was like a force of nature that just wore you down.

Moses’ skillset, centered on rejecting paint visitors, grabbing rebounds, taking close shots, seems to be a lost art in today’s NBA. Is there any player that perhaps, not to the same level of course, but one that perhaps keeps his example alive in the modern Association?

PK: That’s a good question. I don’t know, it’s it’s hard to say, because the game has changed so much and if I think if Moses played now, he would play somewhat differently. He would have adapted his skill set and become more of a passer and a little more of a shooter and things like that. [New York Knicks center] Mitchell Robinson has got the size and the energy. I think that’s a fair one. He’s not really as skilled, particularly offensively, as Moses, but yeah, Mitch gets after it.

Speaking of the Knicks, your last book focused on the 1990s editions of that franchise. What were the unique challenges in covering Moses this time around?

PK: The big difference is, it’s such a deep dive on one person With the 90s Knicks, there are a lot of personalities and you go into the personalities, you give background on them.

Take Patrick Ewing. I spoke to Patrick Ewing’s high school coach, Mike Jarvis, about Patrick when he was younger, and I believe I spoke to one other high school teammate and that was kind of it, as far as Patrick Ewing’s childhood, right? Well, for Moses, I spoke to dozens of people from his hometown where he grew up. So it’s just more, which is fun in a way, but it’s different. In the Knicks book, you learn a decent amount about a lot of people, whereas in the Moses book, it’s more about learning a tremendous amount on one person.

On a personal level for you, who or what do you want your next book to focus on?

PK: There’s one person I would like to, and I don’t know if it happened, but someone I’ve been thinking about, at least is Dikembe Mutombo.

That book would go in a different direction. I knew somewhat about Mutombo before he died and then, when he died, I was reading a lot about him. I didn’t realize the extent of his philanthropic work. He built a hospital in his native country, the Congo. There hasn’t been a new hospital in the Congo since the 1960s and there’s been hundreds of thousands of people treated there. The hospitals there, you can’t even call them like a walk-in clinic, they didn’t really even have medicine. Typically hospitals are built by governments or like massive corporations, but Dikembe did it all himself.

He put a lot of his money into it and raised the rest from friends and sponsors or whatever. But it didn’t stop there. He started a coffee company in Africa to employ women from poor countries. It’s a long list and he would travel the continent regularly and do all kinds of things there. Just as big as he was physically, I think he was even more of a giant as a person. The things you hear about him are that he was just a one of a kind person. I think it’d be fun. He was a great player. He was a great personality. People know him from the Geico commercials. So I thought about that.

It’d be difficult. I was just telling you how, like with Moses, I spoke to dozens of people from his hometown. I think it’d be very difficult to talk to people that came up with him the Congo. How do I get in touch with those people? They probably don’t speak English, even the research.

The other thing with Moses is okay, so I talked to some, a ton of people, but I also, like, I read every I read tons of articles from his hometown newspaper. I got a lot of information about his high school years. I got court documents on Moses and about his divorce and stuff like that, his date of birth, his parents, marriage license, all kinds of stuff. That kind of stuff, I think would be very difficult to get from the Congo. I’m guessing they don’t have a local newspaper that covered all his high school exploits.

I just started reading when he died last year and I was like, wow, this guy is much more interesting than I realized as I read more. He came to the United States, not on a basketball scholarship, on a USAID scholarship to play, to study medicine, to be a doctor. He actually, I don’t know if it’s sounds kind of like the equivalent of like the SATs, but he basically scored off the charts in the Congo national exam.

That got him a scholarship, a USAID scholarship. I think the President has now terminated that program, but that got him a USAID scholarship to come to Georgetown. [Georgetown head coach] John Thompson saw him on campus and went up to him and said “Son, you need to play basketball.” That’s how his basketball career started. So he’s a really, really interesting guy. I just don’t know if I could make it work.

Geoff Magliocchetti is on X @GeoffJMags